Author’s Note: Some time ago I read a review/historical commentary piece regarding Rabbitt’s

second album which I felt rather missed the point, repeatedly, in regards to

cultural criticism and thus I was further inspired to share my own essay which I have been working on for several years now. So without further

ado…

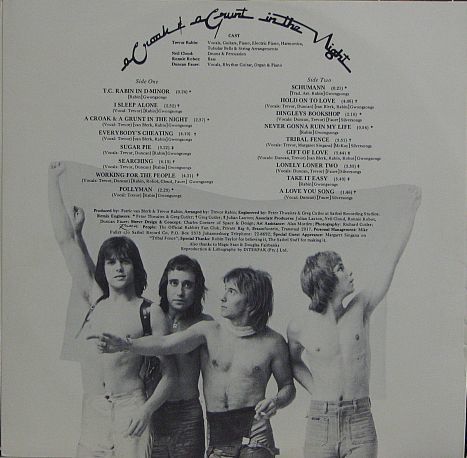

A Boy and his Strat: Trevor’s teen idol cheesecake moment for the cover of

A Croak & A Grunt in the Night.

A Croak & A Grunt in the Night.

In this blog you will read (if you so choose) many words in

praise of the Lekker Four, as I call them, and the reason why is best summed up

in this blurb from RetroFresh, the South African-based imprint which reissued Rabbitt’s full-length studio albums a number of years ago:

Three decades ago,

Rabbitt ruled South Africa for five short years: they were dazzling on stage,

innovative in the recording studio and a media phenomenon in the press.

In my interview with Trevor – in regards to the

auspices of his career in South Africa – he was very careful to make a

distinction between his role in Rabbitt and his efforts towards other genres

and forms which he was concurrently engaged in:

As far as seriousness

goes playing jazz was purely about the music and had nothing to do with any

marketing strategy or genres, unlike Rabbitt where marketing and packaging were

part of the business.

As an unabashed fan of Rabbitt – the Johannesburg-based group

which Trevor co-founded while still in his teens and which he single-mindedly

propelled to nationwide stardom in the mid-1970s – I have spent a great deal of

time in consideration of their time and place in cultural history, especially

because they inhabited such a strange little bubble, thanks to the isolationist

position granted to South Africa as a result of the practice of apartheid. Within their own fairly brief tenure as the

Best Band in the Land it seems their evolution was sped up, in that I firmly

believe when you compare their two full-length releases – Boys Will Be Boys! (1975) and A

Croak & A Grunt in the Night (1977) – it’s almost as if they were recorded

by two different bands.

And really, it’s not such a farfetched consideration. But more interesting, perhaps, is to

speculate how and why Rabbitt took that overwhelming consensus and used it as a

way to attempt to move beyond the popularity afforded in their home country and

aim for worldwide recognition. Had they

not the edicts against South Africa to battle – as well as internal strife -

who knows what they would have achieved.

But chronicling regarding Trevor’s career involves a lot of what ifs.

Running counter to some past commentary, Rabbitt had a

definite agenda in regards to how they would break big in the nation. Their manager Mike Fuller has admitted that

local girls were encouraged (read: paid) to help build a buzz by fervently screaming

during their sets at Take It Easy, the club in Johannesburg where the band had

a residency circa 1974-75. This practice

caught on for real rather quickly and resulted in the same type of behavior

which doomed the Beatles in regards to live performance. Trevor noted in a 1991 interview that the

audience reaction was a kind of “euphoria…hysteria” wherein the music could not

actually be heard over the screaming.

But touring was necessary in regards to continuing to build upon and

reward the fanbase and so the band did tour regularly right up to the time when

they had planned to travel to the United States. This, of course, never occurred.

But they certainly had created the best product to promote

in the form of their second release, which appealed – much as Trevor himself – on

several different levels, and a serious consideration of the album is long

overdue.

The band knew the stakes were high in regards to their sophomore effort, and this is reflected in

their preparation, as Doug Gordon notes in his article “Working For The People:

The Rabbitt Story:”

The 17 tracks laid down in its

plush new Main Street studio measured up to the standards in Europe and allowed

Trevor to push the creative limits. He worked with Duncan to reshape his songs

the Rabbitt way. Neil analyzed Nigel Olssen’s drumming on Elton John’s

top-selling Goodbye Yellow Brick Road double album and added it to his

own technique.

Although any SA-based band could readily cop the conventions

of others half a world away, Rabbitt was one of the few bands who could take

various influences and build upon them to create a unique signature and

appeal. In a country with an incredibly

circumscribed media presence – subject to government censoring at any time – they

were the kind of larger-than-life figures both music and image-wise which their

target audience had longed for, and every aspect of the recording – from music and performances to arrangement to production to album

artwork to promotion – reflected this fact.

With the perspective of time this album is now as viewed Rabbitt's magnum

opus, but not merely because they never recorded another full-length release as a foursome. Their ambition, taste,

and musical intelligence was bound to provide a grander scale which then

supported the whole of their experience and ability in the creation of the

recording.

There are certain subjects and forms which inform Trevor’s

compositional aims in that timeframe (and thus are reflected on this album),

and Trevor has acknowledged that he experienced an introspective period in his

adolescence which led to lyrics addressing the world in which he lived, and for

which he longed to see made whole, as well as seeking those situations/influences

beyond his middle-class existence (having noted in a recent interview that he

often frequented the shebeens – illegal bars in Soweto – both to listen to

music and flout the law in playing onstage with black musicians). Beyond the writing of “(Wake Up!) State Of

Fear” during his tenure in Freedom’s Children in 1972, there were other songs

which expressed the frustration and yearning of living in a nation in the

shadow of apartheid and one of these which appears on the album is an accomplished piece of social

commentary. Another song crossed both

the color line and the boundary of what would be considered acceptable material

for a popular album in its inclusion.

And it’s to the credit of both the band and their production team that

they took those challenges straight on, they didn’t back down in

the face of possible criticism and controversy.

Certainly their enormous popularity – unprecedented for its time –

granted them a Teflon-like veneer in regard to whatever they did.

What is important to consider in regards to Croak is not that it is merely good music in a larger historical

context, but that it is one of the best recordings to ever come out of the

South African music scene in the Apartheid era as well as a historical document

which conclusively illustrates the inherent talent of Trevor Rabin long before

the world would know of him as the wunderkind and creator of the Million Dollar

Riff, courtesy of a song which endures because at its core it transcends

considerations of history, genre, and trends.

So those opinions which are likely to express such sentiments as

“Rabbitt were actually a good band despite their teenybopper image,” are

extremely reductionist, in my opinion.

Rabbitt was the best rock

band in the nation who did certainly did court a female audience but did not

wholly pander to that construct, and the proof lies in the music. Croak does justice to their position, historically, as well as provides enjoyment and

insight even now and in a way Rabinites will not experience with any other of

Trevor’s records, and as such should be celebrated and cherished.

Although I tend to recommend both Rabbitt albums to

potential collectors, Croak is the

one which will stand up to repeated listening and also critical appraisal. But let's start strictly on face value with that infamous cover which continues to enthrall Trevor's fans over thirty years later, designed - as was Boys Will Be Boys! - by Patric van Blerk's former partner Charles Coetzee, and all the boys are nude (but not naked, there is a difference), by turns seductive and coy...at least until we get to Ronnie on the back cover, which is ultimately meant to poke fun at the concept, I'm thinking. However the international version of the album did not include the gatefold or the inner sleeve with additional photographs and lyrics so therefore the best version of the vinyl for collectors to obtain is the original South African release. The RetroFresh CD also contains all the applicable artwork. But beyond the obvious sexuality of the cover concept it's a slick and shiny package, right down to the label on the vinyl which is specially printed with an action pose of the band, proclaiming this is their record entire:

The album's sides are divided up in regards to vocal duties as Rabbitt possessed two singers. Side One is dominated by Trevor's lead vocals, whereas Side Two is mostly devoted to Duncan with the exception of two tracks, plus three instrumentals.

The album opens with two tracks which are wholly Trevor's in regards to both composition and ambition: the classical-transposed-for-electric guitar "T.C. Rabin in D-Minor" and "I Sleep Alone," a ballad which displays moody chromatics with an orchestral backdrop and the chiming of tubular bells, featuring Trevor's two voices: intricate classical-style guitar and his lush tenor supporting lovelorn (and more adult-minded) lyrics. This choice of sequencing illustrates the overall serious tone the production team meant to convey, that the album did not have to begin with a hit single, but rather build from a more naturally dramatic introduction.

From there it slides into the pocket with the title track, a slinky playful R&B-flavored wink and a nod to salacious activities, again another indication that the former boys had now become men and were looking to express themselves beyond the sweetness of pop into something more sophisticated. The accent of strings as a melodic refrain are a hallmark of Trevor's sensibilities as an arranger, appreciating the emotional resonance a good string section can offer, whatever mood may be required. As Doug Gordon points out: Trevor was as clever by then with string arrangements as Keith Richards was with guitar riffs, and he’s built his career on that understanding ever since.

This is followed by "Everybody's Cheating" - which was later covered by Rick Springfield on his album Beautiful Feelings - and although poignant there's a bit of dramatic irony displayed in such a passionate statement of devotion which then moves into a cynical refrain. I am thankful for a document of those days when Trevor could effortlessly hit the high notes - as he does when he sings and I believe I love you till my life is done - and the arrangement of stacked harmonies and buildup which then drops out at the end to just his voice and piano is gorgeous.

These songs are yet another reminder of how well Trevor and Patric van Blerk collaborated as songwriters, their body of work a perfect marriage of lyric and melody.

"Sugar Pie" is probably the first-ever example of Trevor composing a "fake out" (see: "Owner of a Lonely Heart") in that the introduction is completely different to the body of the song, so his orchestral sensibilities are evident in its prog-type overture, which then segues into more of a glam-like song. The call-and-response of Trevor and Duncan's vocals on the bridge and refrain emphasizes the contrast between their voices and is another great arrangement choice which became - even for as short a time as it was - a very definable element of their overall sound.

"Searching" is another big ballad with an anthemic chorus, and it's one of my favorites for reasons of personal taste. Primarily because Trevor sings in a way which was a specific stylistic choice but also, by 1979 his register would undergo a complete change: dropping down and developing a bit more grit, and so it's a wonderful snapshot of a bygone era: sensuous and breathy and wholly romantic. I wonder why those fans who are often expressing their love of Trevor's vocals don't mention the Rabbitt albums so much, because in my estimation his mid-70s range is the one which engenders that swoon-y devotion which long-time fans possess. Lyrically, the song offers a bit of an insight into the "mad years" as Trevor has described them:

Now I don't mind

the way things are.

Wake up in the evening,

breakfast in the bar.

The album's sides are divided up in regards to vocal duties as Rabbitt possessed two singers. Side One is dominated by Trevor's lead vocals, whereas Side Two is mostly devoted to Duncan with the exception of two tracks, plus three instrumentals.

The album opens with two tracks which are wholly Trevor's in regards to both composition and ambition: the classical-transposed-for-electric guitar "T.C. Rabin in D-Minor" and "I Sleep Alone," a ballad which displays moody chromatics with an orchestral backdrop and the chiming of tubular bells, featuring Trevor's two voices: intricate classical-style guitar and his lush tenor supporting lovelorn (and more adult-minded) lyrics. This choice of sequencing illustrates the overall serious tone the production team meant to convey, that the album did not have to begin with a hit single, but rather build from a more naturally dramatic introduction.

From there it slides into the pocket with the title track, a slinky playful R&B-flavored wink and a nod to salacious activities, again another indication that the former boys had now become men and were looking to express themselves beyond the sweetness of pop into something more sophisticated. The accent of strings as a melodic refrain are a hallmark of Trevor's sensibilities as an arranger, appreciating the emotional resonance a good string section can offer, whatever mood may be required. As Doug Gordon points out: Trevor was as clever by then with string arrangements as Keith Richards was with guitar riffs, and he’s built his career on that understanding ever since.

This is followed by "Everybody's Cheating" - which was later covered by Rick Springfield on his album Beautiful Feelings - and although poignant there's a bit of dramatic irony displayed in such a passionate statement of devotion which then moves into a cynical refrain. I am thankful for a document of those days when Trevor could effortlessly hit the high notes - as he does when he sings and I believe I love you till my life is done - and the arrangement of stacked harmonies and buildup which then drops out at the end to just his voice and piano is gorgeous.

These songs are yet another reminder of how well Trevor and Patric van Blerk collaborated as songwriters, their body of work a perfect marriage of lyric and melody.

"Sugar Pie" is probably the first-ever example of Trevor composing a "fake out" (see: "Owner of a Lonely Heart") in that the introduction is completely different to the body of the song, so his orchestral sensibilities are evident in its prog-type overture, which then segues into more of a glam-like song. The call-and-response of Trevor and Duncan's vocals on the bridge and refrain emphasizes the contrast between their voices and is another great arrangement choice which became - even for as short a time as it was - a very definable element of their overall sound.

"Searching" is another big ballad with an anthemic chorus, and it's one of my favorites for reasons of personal taste. Primarily because Trevor sings in a way which was a specific stylistic choice but also, by 1979 his register would undergo a complete change: dropping down and developing a bit more grit, and so it's a wonderful snapshot of a bygone era: sensuous and breathy and wholly romantic. I wonder why those fans who are often expressing their love of Trevor's vocals don't mention the Rabbitt albums so much, because in my estimation his mid-70s range is the one which engenders that swoon-y devotion which long-time fans possess. Lyrically, the song offers a bit of an insight into the "mad years" as Trevor has described them:

Now I don't mind

the way things are.

Wake up in the evening,

breakfast in the bar.

Which he then counters with but somehow this just can't go on forever and it seems to me he has always practiced a certain prescience in regards to his own situation.

The last two songs are a pair which address the concerns of social justice, but in such a way that it's not wholly overt. To challenge the government would have brought a host of penalties and so one had to be clever. "Working For The People" is credited to the entire band with a co-lead vocal by Trevor and Duncan and was inspired by the Soweto riots of 1976, even as it seems to be merely about the struggles of a young band trying to make it big. It's a call for unity, because the "people" of which they sing is every member of the South African population, not merely the white hegemony who were the target of those riots. It's an anthem which blends a number of production elements (and also includes string accents rubbing shoulders with distorted guitars) meant to be chanted along to when one heard it on the radio or in live performance. There's even a bit of humor as the na-na-na refrain just sort of falls apart at the end.

"Pollyman" is, in my estimation, a mix of social satire with a metaphorical description of how the philosophy of apartheid literally warped the minds of those who adopted it. The music is purposely genteel and nostalgic - down to the creak of a rocking chair out on the proverbial veranda - while Trevor sings of a man who struggles with his own conscience (but also taking a moment to tease his bass player who apparently did not rise before noon):

But now we see such an academic mind being programmed to their game.

A jigsaw puzzle where the pieces don't fit, we'll jam them all the same.

Where the big ones all can gain -

This is - especially the second line - a perfect description of the cognitive dissonance of apartheid as a social system. South African society was being supported literally upon the backs of its oppressed peoples, and Trevor lends his own voice to the appeal for humanity. In the fade out we hear conversation mixed in with the sound of a radio broadcast diatribe, which appears to be Trevor (who I believe has a little-known talent for impersonation). But this wasn't the first time he had addressed the subject, "Savage" from Boys Will Be Boys! is also about the injustices of apartheid, but again written in such a way as to be interpreted on several levels.

Side Two begins with "Schumann" which I believe is an arrangement for guitar of the opening theme of "Kinderszenen" by German composer Robert Schumann. Granted, it is just a fragment, and anyone in possession of the correct attribution please email me at the address in my introduction banner and let me know. But this illustrates both Trevor's classical training and his desire to maintain such forms even in a rock n'roll setting, which he would further elaborate upon throughout his career.

The last two songs are a pair which address the concerns of social justice, but in such a way that it's not wholly overt. To challenge the government would have brought a host of penalties and so one had to be clever. "Working For The People" is credited to the entire band with a co-lead vocal by Trevor and Duncan and was inspired by the Soweto riots of 1976, even as it seems to be merely about the struggles of a young band trying to make it big. It's a call for unity, because the "people" of which they sing is every member of the South African population, not merely the white hegemony who were the target of those riots. It's an anthem which blends a number of production elements (and also includes string accents rubbing shoulders with distorted guitars) meant to be chanted along to when one heard it on the radio or in live performance. There's even a bit of humor as the na-na-na refrain just sort of falls apart at the end.

"Pollyman" is, in my estimation, a mix of social satire with a metaphorical description of how the philosophy of apartheid literally warped the minds of those who adopted it. The music is purposely genteel and nostalgic - down to the creak of a rocking chair out on the proverbial veranda - while Trevor sings of a man who struggles with his own conscience (but also taking a moment to tease his bass player who apparently did not rise before noon):

But now we see such an academic mind being programmed to their game.

A jigsaw puzzle where the pieces don't fit, we'll jam them all the same.

Where the big ones all can gain -

This is - especially the second line - a perfect description of the cognitive dissonance of apartheid as a social system. South African society was being supported literally upon the backs of its oppressed peoples, and Trevor lends his own voice to the appeal for humanity. In the fade out we hear conversation mixed in with the sound of a radio broadcast diatribe, which appears to be Trevor (who I believe has a little-known talent for impersonation). But this wasn't the first time he had addressed the subject, "Savage" from Boys Will Be Boys! is also about the injustices of apartheid, but again written in such a way as to be interpreted on several levels.

Side Two begins with "Schumann" which I believe is an arrangement for guitar of the opening theme of "Kinderszenen" by German composer Robert Schumann. Granted, it is just a fragment, and anyone in possession of the correct attribution please email me at the address in my introduction banner and let me know. But this illustrates both Trevor's classical training and his desire to maintain such forms even in a rock n'roll setting, which he would further elaborate upon throughout his career.

"Hold On To Love" is full of space and gauzy diffused layers of vocals and instrumentation, creating an overall mood of romantic longing, yet another great collaboration of Trevor and Patric. The chorus is just a simple refrain (and I can imagine thousands of girls singing along with it) but perhaps the best part is the pure rock n'roll scream Duncan lets out at the end just before the fade out. Ronnie also stands out on this song, his bass line providing an anchor amid the delicacy.

Ever a band to take advantage of cross-promotional

opportunities, Duncan has his moment in the greater media spotlight as the

composer of the theme song for the SABC sitcom Dingley’s Bookshop. Just as "Charlie" was included in the first film Trevor was to score the previous year, Death of a Snowman, this was another

chance for Rabbitt to be ubiquitous in SA popular culture and the boys mimed to

comedic affect in the opening sequence amongst the denizens of a certain

bookseller in Pietermaritzburg. The

track itself is probably the most obvious nod to Duncan’s primary influence, the Beatles, as a spritely piano-driven melody is augmented with whimsy:

staccato bursts of guitar, sound effects, and high harmonies on the refrain in addition to Duncan's Lennonesque vocal. The band also appeared - as themselves - in an episode of the show, prompting Trevor to dub himself and his bandmates "the world's worst actors."

Cross-promotional opportunities: Rabbitt appearing in the opening

credits (and performing the theme song) of Dingley’s Bookshop.

The second of the Side Two instrumentals is "Never Gonna Ruin My Life" and it's a little slice of the way Trevor liked to pair guitar with violin, set to Neil's rock-solid 4/4 beat. Throughout the album it's obvious that the band is thoroughly focused on delivering their best performances, but they also seem equally effortless in the way in which they mesh and meld; given that Trevor, Neil and Ronnie had spent nearly the greater part of their lives up to that point playing together.

If there was ever a declarative of the social conscience of the members of Rabbitt, it is displayed in their decision to cover the song "Tribal Fence" written by Ramsay MacKay, once the creative lynchpin of Freedom's Children. Croak was mixed in part by yet another member of that band, Julian Laxton (who would also go on to have a career as a solo artist as well as a producer), and as long-time fans know, Trevor and Ronnie were also members for a year, though by then that version contained only one original member. Freedom's Children was one of the first anti-apartheid rock bands in South Africa, continually flouting the establishment, and in that spirit - on record - Rabbitt also decided to cross the color line and record the song as a collaboration with Margaret Singana, one of the most popular black vocalists in the country on both sides of the charts. Trevor and Patric were the vehicle of her Top 40 career, providing co-production/arranging/songwriting/performance support on a series of albums for Jo'Burg Records (which were distributed internationally by Casablanca). Her fans called her Lady Africa and her powerful voice rises up like an charging army to ask when we will be/past tribal fence/and family tree. Singana also covered the song as the title track of her 1977 release. Trevor's arrangement of the song is more akin to free jazz than the heavy psychedelica of the original. But make no mistake: this was an incredibly audacious move on their part - the biggest band in the country and number one teen idols bringing a taste of revolution into every white household: moderate, liberal and conservative.

"Gift Of Love" evokes a spacy airy mood with layers of guitars, synths and electric piano surrounding Duncan for his turn in the spotlight as the object of fantasy which these songs were meant to evoke. The way in which Duncan and Trevor harmonize on the refrain is simply dreamy...and sure, you can say I'm biased but there's no better word for it. This is followed by "Lonely Loner Two" and it starts out with another bit of humor - as Trevor's count-off is interrupted by a belch from Ronnie - and is another mid-tempo Beatlesque excursion which would come to define Duncan's songwriting style on the subsequent album written and recorded without Trevor, Rock Rabbitt.

"Take It Easy," likely named for the aforementioned club where Rabbitt built their core audience before conquering the country entire, displays interesting elements of classical and progressive rock in its three minutes, as well as some fleet-fingered guitar heroics from Trevor.

"A Love You Song" concludes Side Two and is a sweet tribute to the wild ride entire, with Duncan commenting on how amazing it is to make music which has touched the lives of so many people. It is recorded in such a way that it sounds like he's playing in a club at the end of the night, after the crowd has departed, with a guitar voicing harmonizing with the piano. But in hindsight there is a bittersweet quality to it even as it celebrates a dream come true. It is, however, the perfect ending for the album: a moment of reflection and gratitude.

Trevor and Duncan both thought well enough of this album that they would later cover themselves: Duncan performing "Working For The People" during his stint with The Rollers (it would appear on their album Voxx), and Trevor would redo "Hold On To Love" as "Hold On To Me" for Can't Look Away with revised lyrics and Duncan providing backing vocals once more. Croak would go on to win a Sarie - as did Boys Will Be Boys! the previous year - for Best Contemporary Pop Album, capping off its nationwide success both critical and popular. But although all looked rosy for the boys' future, the center could not hold. As we see in this clip, which surfaced a few years ago (from what appears to be a documentary), the deal the band inked with Capricorn Records - one of the first mainstream independent record labels - for worldwide distribution and touring support fell apart before it was even fully realized, the result of both international censure and internal struggles.

The band had been courted by Frank Fenter, who possessed a unique understanding of the need for Rabbitt to break worldwide, as Candice Dyer writes in her 2010 article, "Frank Fenter: The Wizard Who Might Have Saved Capricorn:"

But even with the brief bright promise displayed to a nation of devotees, and those elsewhere willing to adopt the band as their own (they developed a following in Japan through press coverage and record sales, for example), Croak is a record which can forever stand as a benchmark in Trevor's discography; an example of how Rabbitt was so successful all those years ago, and why a good portion of Trevor's fanbase hails from one particular spot on the map, proud that he is one of their special sons. Though it's true that no one can dictate the tastes of any of Trevor's fans I will say that if you are a fan and you do not have this record (or you only bought it for the cover), you should do yourself a favor and experience yet another reason to be amazed by the Maestro, because those abilities and instincts and that intelligence and charisma which would finally win him worldwide recognition, a decade later, was entirely apparent in his work with Rabbitt and especially on this, their very best album.

Rabbitt Rules, OK? You bet they do!

The second of the Side Two instrumentals is "Never Gonna Ruin My Life" and it's a little slice of the way Trevor liked to pair guitar with violin, set to Neil's rock-solid 4/4 beat. Throughout the album it's obvious that the band is thoroughly focused on delivering their best performances, but they also seem equally effortless in the way in which they mesh and meld; given that Trevor, Neil and Ronnie had spent nearly the greater part of their lives up to that point playing together.

If there was ever a declarative of the social conscience of the members of Rabbitt, it is displayed in their decision to cover the song "Tribal Fence" written by Ramsay MacKay, once the creative lynchpin of Freedom's Children. Croak was mixed in part by yet another member of that band, Julian Laxton (who would also go on to have a career as a solo artist as well as a producer), and as long-time fans know, Trevor and Ronnie were also members for a year, though by then that version contained only one original member. Freedom's Children was one of the first anti-apartheid rock bands in South Africa, continually flouting the establishment, and in that spirit - on record - Rabbitt also decided to cross the color line and record the song as a collaboration with Margaret Singana, one of the most popular black vocalists in the country on both sides of the charts. Trevor and Patric were the vehicle of her Top 40 career, providing co-production/arranging/songwriting/performance support on a series of albums for Jo'Burg Records (which were distributed internationally by Casablanca). Her fans called her Lady Africa and her powerful voice rises up like an charging army to ask when we will be/past tribal fence/and family tree. Singana also covered the song as the title track of her 1977 release. Trevor's arrangement of the song is more akin to free jazz than the heavy psychedelica of the original. But make no mistake: this was an incredibly audacious move on their part - the biggest band in the country and number one teen idols bringing a taste of revolution into every white household: moderate, liberal and conservative.

"Gift Of Love" evokes a spacy airy mood with layers of guitars, synths and electric piano surrounding Duncan for his turn in the spotlight as the object of fantasy which these songs were meant to evoke. The way in which Duncan and Trevor harmonize on the refrain is simply dreamy...and sure, you can say I'm biased but there's no better word for it. This is followed by "Lonely Loner Two" and it starts out with another bit of humor - as Trevor's count-off is interrupted by a belch from Ronnie - and is another mid-tempo Beatlesque excursion which would come to define Duncan's songwriting style on the subsequent album written and recorded without Trevor, Rock Rabbitt.

"Take It Easy," likely named for the aforementioned club where Rabbitt built their core audience before conquering the country entire, displays interesting elements of classical and progressive rock in its three minutes, as well as some fleet-fingered guitar heroics from Trevor.

"A Love You Song" concludes Side Two and is a sweet tribute to the wild ride entire, with Duncan commenting on how amazing it is to make music which has touched the lives of so many people. It is recorded in such a way that it sounds like he's playing in a club at the end of the night, after the crowd has departed, with a guitar voicing harmonizing with the piano. But in hindsight there is a bittersweet quality to it even as it celebrates a dream come true. It is, however, the perfect ending for the album: a moment of reflection and gratitude.

Trevor and Duncan both thought well enough of this album that they would later cover themselves: Duncan performing "Working For The People" during his stint with The Rollers (it would appear on their album Voxx), and Trevor would redo "Hold On To Love" as "Hold On To Me" for Can't Look Away with revised lyrics and Duncan providing backing vocals once more. Croak would go on to win a Sarie - as did Boys Will Be Boys! the previous year - for Best Contemporary Pop Album, capping off its nationwide success both critical and popular. But although all looked rosy for the boys' future, the center could not hold. As we see in this clip, which surfaced a few years ago (from what appears to be a documentary), the deal the band inked with Capricorn Records - one of the first mainstream independent record labels - for worldwide distribution and touring support fell apart before it was even fully realized, the result of both international censure and internal struggles.

The band had been courted by Frank Fenter, who possessed a unique understanding of the need for Rabbitt to break worldwide, as Candice Dyer writes in her 2010 article, "Frank Fenter: The Wizard Who Might Have Saved Capricorn:"

He understood how it (segregation) ultimately impoverishes everyone, including the oppressors, because he grew up in a place that was even more violently stratified than this cotton-belt town: South Africa in the darkest days of apartheid. He also knew — from sneaking into blacks-only nightclubs and presenting, like some ghostly apparition, the only white face around a drum-circled bonfire on the ragged outskirts of Johannesburg — about the unifying power of music.Even as their future was planned as a collective, each member was also enticed to sign solo deals, and Trevor was the first to decide to walk away, though he would not officially emigrate to London until a year later. The remaining members attempted to carry on, and while Rock Rabbitt is a sophisticated collection of pop-rock, it is lacking Trevor's touch, and fans knew it too. Having to compete with Trevor's solo debut, Beginnings, meant a war for the hearts and loyalties of the fans they had won together. Trevor commented during my interview with him that the split was akin to a divorce, given the heightened emotions involved at that time.

But even with the brief bright promise displayed to a nation of devotees, and those elsewhere willing to adopt the band as their own (they developed a following in Japan through press coverage and record sales, for example), Croak is a record which can forever stand as a benchmark in Trevor's discography; an example of how Rabbitt was so successful all those years ago, and why a good portion of Trevor's fanbase hails from one particular spot on the map, proud that he is one of their special sons. Though it's true that no one can dictate the tastes of any of Trevor's fans I will say that if you are a fan and you do not have this record (or you only bought it for the cover), you should do yourself a favor and experience yet another reason to be amazed by the Maestro, because those abilities and instincts and that intelligence and charisma which would finally win him worldwide recognition, a decade later, was entirely apparent in his work with Rabbitt and especially on this, their very best album.

Rabbitt Rules, OK? You bet they do!